Prevezë: 12 Vjesht’ e tretë 1809

Zonjës Byron,

Po bëhet një kohë e gjatë që gjëndem në Turqi; qyteti nga i cili u shkruaj qënndron buzë Adriatikut, por unë e pash më mirë këtë provincë shqipëtare kur vizitova pashanë.

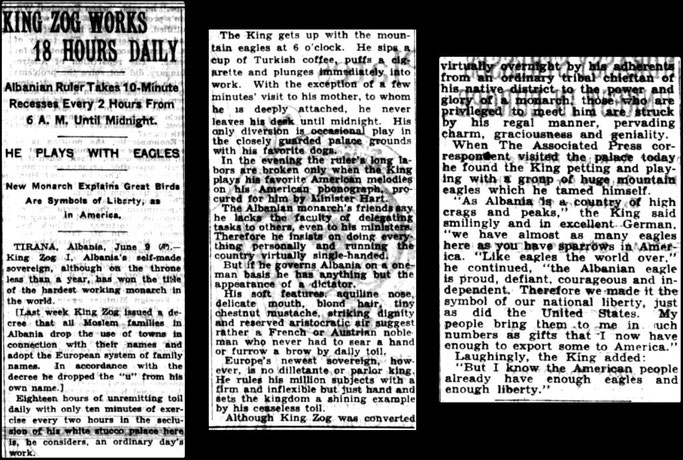

Nga nisia Malta u-nisa me 24 vjesht’ e parë me vaporin luftëtar Marimanga” , dhe pas tetë ditësh hariva në Prevezë. Që këtej barita edhe 150 mila brënda në Shqipëri, për në Tepelenë, ku gjëndet pallati i Lartësis’ së Tij, dhe ndënja tri ditë. Pasha quhet Ali, dhe është i njohur si njeri me virtytete të larta. Ay qeverisë tëre Shqipërinë dhe një pjesë të Maqedhonisë. I biri i tij Veli pasha për të cilin më dha disa letra me rëndësi, qeveris Morenë, dhe është shum’ i dëgjuar n’ Egjyptë. Me një fjalë pashai është një nga njerëzit më të dëgjuar të Imperatorisë otomane.

Kur arriva në Janinë kryeqytet’ i Shqipërisë –mësova se Ali pasha ish me ushtërin’ e tij n’Iliri, ku kish rrethuar Ibrahim pashanë, në fortesën e Beratit. Ay kish dëgjuar se në vendin e tij kish ardhur një ingliz prej soji të madh dhe i kish dhënë urdhër qeveritarit të Janinës që të përkujdeset për mua dhe të më japë ç’më duhet pa kërkuar as një pesësh’ që t’i jap dhurata robërve m’u dha lejë po që të paguanja gjëkafshë në shtëpinë ku isha, nuk m’u dha lejë. Kisha të drejtë të kaloj kuajt’ e pashajt, kështu i kaluar vizitova pallatet e pashajt dhe të nipërve të tij. Këta janë shumë të bukur, dhe të stolisurë me kadifera të mëndafshta. Malet dhe përgjithësisht, vendi këtu ka një bukuri natyrale shumë të madhe, gjër më sot s’e kam parë me no një vent tjatrë.

Pas nëntë ditësh udhëtimi hariva në Tepelenë. Udhëtimi ynë u-ndalua shumë nga shirrat e dëndur që binin.

Asnjë herë nuk’dot’haroj bukurin’ e madhe q’u çfaq përpara syve të mij kur hyra në Tepelenë, në ora pesë të mbrëmauret në perendim të diellit. Ajo bukuri më kujtoj përshkrimin q’i jep Walter Scott-i, Kastelit të Branksomit në vjershën e tij “Këngët e fundit” me tërë feodolizmën e saj.

Shqiptarët (me kostumin’ e tyre të bukur) i cili formohet prej një fustanelle të bardhë, anteri të qëndisur me sërme dhe jelek prej kadifeje të kuqe të qëndisur me gajtane të mendafshtë, kobure dhe jataganë me mill të argjentë etj…më pëlqejnë shumë.

Mua më shpunë në një dhomë të bukur dhe sekrtetari i vezirit ardhi të më pyesë për gjëndjen t’ime.

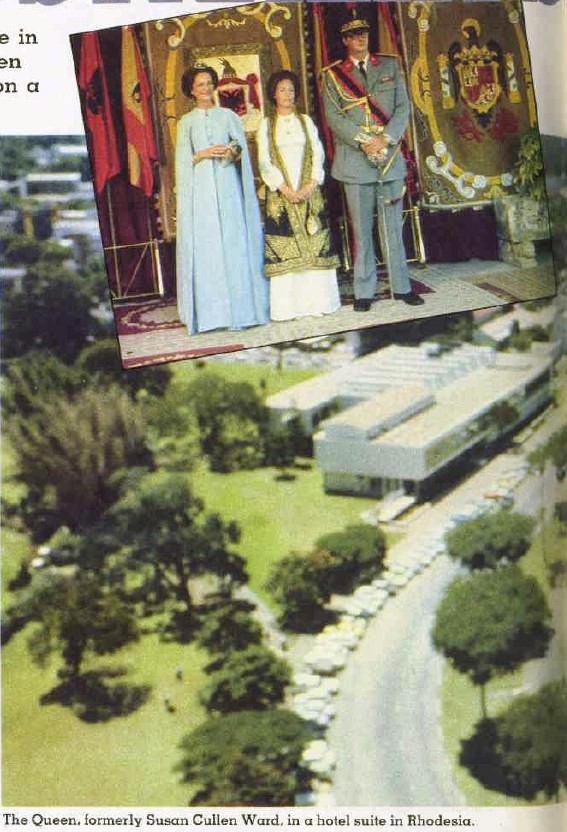

Të nesërmet vizitova Ali pashanë. Ky qe veshur me uniformën zyrtare prej gjenerali, ngjeshur rreth mesit një shpatë të bukur etj.etj…Veziri më priti në një dhomë shumë të bukur, të shtruar me mermer, në mes të cilës ridhte një shatervan. Dhoma qe e stolisur me “kanape”të shtruara me mendafsh. Pashaj më priti duke u-ngritur më këmbë, e cila tregon shënjë nderi, dhe më ftoj që të ri n’anën e djathtë të tij.

Gjithënjë kam si terxhuman një grek, po këtu u hasa me shkronjesin e Ali pashajt Femlario i cili dinte ca latinisht dhe ky më shërbeu për t’u marrë vesh me pashanë. Pyetja e parë që më bëri ish; pse e kam lëne atdheun t’im kaq i ri (këtu njerëzia smundin të kuptojnë se si njeriu mund t’udhëtoj pas deshirës së ti),Pashaj më tha se konsulli ingliz, kapiteni Leek e kish lajmëruar për ardhjen time dhe kish thënë se jam nga një familje e dëgjuar; ky m’u lut t’u dërgoj ngjatjetimet e tij dhe unë po u-u çojë nga emri i Ali pashajt. Më tha se mbeti shumë i kënaqur nga sjelljet e mija dhe m’u lut që sa kohë të gjëndem në vëndin’ e tij ta shikoj atë posi një atë dhe ay mua posi bir.\

Dhe me të vërtëtë, ay sillesh posi një atë, më dërgonte t’ëmbëla, pemë etj.dhe m’u lut që të vinja shpesh mbrëmandent dhe të bisedonim bashkë.

So pashë të mbeturat e qytetit të vjetër Akcium ku Antoni humbi botën. Më tutje duken gërmadhat e qytetit Nikopol, i cili u godit prej imperatorit August si kujtim të fitimit të tij.

Mbase i dua shumë shqiptarët, këta nuk janë të gjithë myslimanë; një pjesë e madhe janë të krishterë, po, përgjithësisht Shqiptarët nuk’ i japin rëndësi fesë, dhe kjo nuk lot nonjë rol për të prishur zakonet kombëtare që kanë. Këta janë ushtarët e parë t’ ushtrisë otomane. Kur udhëtomnja fjeta dy net në një dobojë dhe me të vërtetë po u-them se as më nonjë vënt tjatrë nuk’kam hasur ushtarë më të sjellër se këta me gjith që kam qenë në garnizonet e Maltës dhe të Gibraltarit dhe që kam parë shumë ushtëri të ndryshme si spanjollë, francezë, sicillianë dhe anglikanë. Këtu nuk m’u voth asgjë dhe u ftuash nga ushtarët shqiptarë që të ha dhe të pi bashkë me ta.

Para një jave, nje kryetar shqiptar më mori në shtëpi të tij dhe pasi na dha të tëra sa na duheshin për të ngrënë e për të pirë, mua dhe, mua dhe të pasësëve t’im që janë: një shërbëtor, një grek, dy nga Athina dhe miku im Z.Hobhaus, nuk deshte të marë as një pesësh, për të gjitha ato, përvec se një fletëzë kartë, në të cilën t’i thoasha që mbeta i kënaqur nga pritja e tij, po unë nuk desha që pa paguar gjë të dilnja nga ay njeriu i mirë, dhe kur u luta që të pranonte ca pak të holla ay m’u përgjegj: “Jo, unë dua që të më duani, jo të më paguani”.

Çudi në këtë vent të hollat s’paskan fare vleftë; Kur isha në kryeqytet(Janinë) pas urdhërit të pashajt nuk’pagova asgjë me gjithë që kisha me vethe 16 kuaj dhe 6-7 shpirt.

Pas ca ditësh do të nisem për në Athinë që të mësoj greqishten e re, e cila ka një ndryshim të madh nga e vjetra, me gjithë që të dyja një emrë kanë dhe një gjuhë janë !….

SHËNIM: Kjo letër që Lord Byroni i kishte dërguar nënës së tij para 206 vjetësh, ishte botuar për herë të parë në gjuhën shqipe në vitin 1914 në revistën “Kalendari Kombiar” që në atë kohë botohej në Sofje të Bullgarisë. Kjo letër e poetit të madh Lord Byron u ribotua në gazetën “Dielli”më 25 Nëntor të vitit 1964. Editori i kësaj gazete Dr. Athanas Gegaj botonte dhe ribotonte vazhdimisht letra e shkrime me permbajtje intelektuale. Editori nuk kishte bërë asnjë ndryshim të asaj letre botuar fillimisht në “Kalendarin Kombiar” . Edhe ne iu permbajtëm drejtëshkrimit të asaj kohe. (Gjekë Gjonlekaj).

Prevesa, November 12, 1809

My dear Mother,

I have now been some time in Turkey. The place is on the coast but I have traversed the interior of the province of Albania on a visit to the Pacha. I left Malta in the Spider, a brig of war, on the 21st of September and arrived in eight days at Prevesa. I thence have been about 150 miles as far as Tepaleen, his highness’ country palace, where I staid three days. The name of the Pacha is Ali, and he is considered a man of the first abilities, he governs the whole of Albania (the ancient Illyricum), Epirus and part of Macedonia. His son Velly Pacha, to whom he has given me letters, governs the Morea and he has great influence in Egypt, in short he is one of the most powerful men in the Ottoman empire. When I reached Yanina the capital after a journey of three days over the mountains through country of the most picturesque beauty, I found that Ali Pacha was with his army in Illyricum besieging Ibraham Pacha in the castle of Berat. He had heard that an Englishman of rank was in his dominion and had left orders in Yanina with the Commandant to provide a house and supply me with every kind of necessary, gratis, and though I have been allowed to make presents to the slaves etc. I have not been permitted to pay for a single article of household consumption. I rode out on the vizier’s horses and saw the palaces of himself and grandsons; they are splendid but too much ornamented with silk and gold. I then went over the mountains through Zitza, a village with a Greek monastery (where I slept on my return) in the most beautiful situation (always excepting Cintra in Portugal) I ever beheld. In nine days I reached Tepaleen, our journey was much prolonged by the torrents that had fallen from the mountains and intersected the roads. I shall never forget the singular scene on entering Tepaleen at five in the afternoon as the sun was going down, it brought to my recollection (with some change of dress however) Scott’s description of Branksome Castle in his lay, and the feudal system.

The Albanians in their dresses (the most magnificent in the world, consisting of a long white kilt, gold worked cloak, crimson velvet gold laced jacket and waistcoat, silver mounted pistols and daggers), the Tartars with their high caps, the Turks in their vast pelisses and turbans, the soldiers and black slaves with the horses, the former stretched in groupes in an immense open gallery in front of the palace, the latter placed in a kind of cloister below it, two hundred steeds ready caparisoned to move in a moment, couriers entering or passing out with dispatches, the kettle drums beating, boys calling the hour from the minaret of the mosque, altogether, with the singular appearance of the building itself, formed a new and delightful spectacle to a stranger.

Ali Pasha of Tepelana

(1744-1822)

I was conducted to a very handsome apartment and my health enquired after by the vizier’s secretary “a la mode de Turque.” The next day I was introduced to Ali Pacha. I was dressed in a full suit of staff uniform with a very magnificent sabre etc. The Vizier received me in a large room paved with marble, a fountain was playing in the centre, the apartment was surrounded by scarlet Ottomans, he received me standing, a wonderful compliment from a Mussulman, and made me sit down on his right hand. I have a Greek interpreter for general use, but a Physician of Ali’s named [Seculario?] who understands Latin acted for me on this occasion. His first question was why at so early an age I left my country? (the Turks have no idea of travelling for amusement). He then said the English Minister, Capt. Leake, had told him I was of a great family, and desired his respects to my mother, which I now in the name of Ali Pacha present to you. He said he was certain I was a man of birth because I had small ears, curling hair, and little white hands, and expressed himself pleased with my appearance and garb. He told me to consider him as a father whilst I was in Turkey, and said he looked on me as his son. Indeed he treated me like a child, sending me almonds and sugared sherbet, fruit and sweetmeats twenty times a day. He begged me to visit him often, and at night when he was more at leisure. I then after coffee and pipes retired for the first time. I saw him thrice afterwards. It is singular that the Turks who have no hereditary dignities and few great families except the Sultan’s pay, so much respect to birth, for I found my pedigree more regarded than even my title. His Highness is sixty years old, very fat and not tall, but with a fine face, light blue eyes and a white beard, his manner is very kind and at the same time he possesses that dignity which I find universal amongst the Turks. He has the appearance of anything but his real character, for he is a remorseless tyrant, guilty of the most horrible cruelties, very brave and so good a general, that they call him the Mahometan Buonaparte. Napoleon has twice offered to make him King of Epirus, but he prefers the English interest and abhors the French as he himself told me. He is of so much consequence that he is much courted by both, the Albanians being the most warlike subjects of the Sultan, though Ali is only nominally dependent on the Porte. He has been a mighty warrior, but is as barbarous as he is successful, roasting rebels etc. etc. Bonaparte sent him a snuffbox with his picture. He said the snuffbox was very well, but the picture he could excuse, as he neither liked it nor the original. His ideas of judging of a man’s birth from ears, hands etc. were curious enough. To me he was indeed a father, giving me letters, guards, and every possible accommodation. Our next conversations were of war and travelling, politics and England. He called my Albanian soldier who attends me, and told him to protect me at all hazards. His name is Viscillie and like all the Albanians, he is brave, rigidly honest, and faithful, but they are cruel though not treacherous, and have several vices, but no meannesses. They are perhaps the most beautiful race in point of countenance in the world, their women are sometimes handsome also, but they are treated like slaves, beaten and in short complete beasts of burthen, they plough, dig and sow, I found them carrying wood and actually repairing the highways. The men are all soldiers, and war and the chase their sole occupations. The women are the labourers, which after all is no great hardship in so delightful a climate.

Yesterday the 11th November, I bathed in the sea, today it is so hot that I am writing in a shady room of the English Consul’s with three doors wide open, no fire or even fireplace in the house except for culinary purposes […]

Today I saw the remains of the town of Actium near which Anthony lost the world in a small bay where two frigates could hardly manoeuvre, a broken wall is the sole remnant. On another part of the gulph stand the ruins of Nicopolis built by Augustus in honour of his victory. Last night I was at a Greek marriage, but this and 1000 things more I have neither time or space to describe. I am going tomorrow with a guard of fifty men to Patras in the Morea, and thence to Athens where I shall winter.

Two days ago I was nearly lost in a Turkish ship of war owing to the ignorance of the captain and crew though the storm was not violent. Fletcher yelled after his wife, the Greeks called on all the Saints, the Mussulmen on Alla, the Captain burst into tears and ran below deck telling us to call on God, the sails were split, the mainyard shivered, the wind blowing fresh, the night setting in, and all our chance was to make Corfu which is in possession of the French, or (as Fletcher pathetically termed it) “a watery grave.” I did what I could to console Fletcher but finding him incorrigible, wrapped myself up in my Albanian capote (an immense cloak) and lay down on deck to wait the worst. I have learnt to philosophize on my travels, and if I had not, complaint was useless. Luckily the wind abated and only drove us on the coast of Suli on the main land where we landed and proceeded by the help of the natives to Prevesa again; but I shall not trust Turkish sailors in future, though the Pacha had ordered one of his own galleots to take me to Patras. I am therefore going as far as Missolonghi by land and there have only to cross a small gulph to get to Patras. Fletcher’s next epistle will be full of marvels. We were one night lost for nine hours in the mountains in a thunder storm, and since nearly wrecked. In both cases Fletcher was sorely bewildered, from apprehensions of famine and banditti in the first, and drowning in the second instance. His eyes were a little hurt by the lightning or crying (I don’t know which) but are now recovered. When you write address to me at Mr. Strané’s English Consul, Patras, Morea.

I could tell you I know not how many incidents that I think would amuse you, but they crowd on my mind as much as would swell my paper, and I can neither arrange them in the one, or put them down on the other, except in the greatest confusion and in my usual horrible hand. I like the Albanians much, they are not all Turks, some tribes are Christians, but their religion makes little difference in their manner or conduct; they are esteemed the best troops in the Turkish service. I lived on my route two days at once, and three days again in a Barrack at Salora, and never found soldiers so tolerable, though I have been in the garrisons of Gibraltar and Malta and seen Spanish, French, Sicilian and British troops in abundance. I have had nothing stolen, and was always welcome to their provision and milk. Not a week ago, an Albanian chief (every village has its chief who is called Primate) after helping us out of the Turkish galley in her distress, feeding us and lodging my suite consisting of Fletcher, a Greek, two Albanians, a Greek priest and my companion Mr. Hobhouse, refused any compensation but a written paper stating that I was well received, and when I pressed him to accept a few sequins, “no,” he replied, “I wish you to love me, not to pay me.” These were his words. It is astonishing how far money goes in this country, while I was in the capital, I had nothing to pay by the vizier’s order, but since, though I have generally had sixteen horses and generally six or seven men, the expence has not been half as much as staying only three weeks in Malta, though Sir A. Ball, the governor, gave me a house for nothing, and I had only one servant. By the bye I expect Hanson to remit regularly, for I am not about to stay in this province for ever, let him write to me at Mr. Strané’s, English Consul, Patras.

The fact is, the fertility of the plains are wonderful, and specie is scarce, which makes this remarkable cheapness. I am now going to Athens to study modern Greek which differs much from the ancient though radically similar. I have no desire to return to England, nor shall I unless compelled by absolute want and Hanson’s neglect, but I shall not enter Asia for a year or two as I have much to see in Greece and I may perhaps cross into Africa at least the Egyptian part. Fletcher like all Englishmen is very much dissatisfied, though a little reconciled to the Turks by a present of eighty piastres from the vizier, which if you consider everything and the value of specie here is nearly worth ten guineas English. He has suffered nothing but from cold, heat, and vermin which those who lie in cottages and cross mountains in a wild country must undergo, and of which I have equally partaken with himself, but he is not valiant, and is afraid of robbers and tempests. I have no one to be remembered to in England, and wish to hear nothing from it but that you are well, and a letter or two on business from Hanson, whom you may tell to write. I will write when I can, and beg you to believe me,

your affectionate son,

BYRON

P.S. I have some very “magnifique” Albanian dresses, the only expensive articles in this country. They cost 50 guineas each and have so much gold they would cost in England two hundred. I have been introduced to Hussein Bey, and Mahmout Pacha, both little boys, grandchildren of Ali at Yanina. They are totally unlike our lads, have painted complexions like rouged dowagers, large black eyes and features perfectly regular. They are the prettiest little animals I ever saw, and are broken into the court ceremonies already. The Turkish salute is a slight inclination of the head with the hand on the breast, intimates always kiss. Mahmout is ten years old and hopes to see me again, we are friends without understanding each other, like many other folks, though from a different cause. He has given me a letter to his father in the Morea, to whom I have also letters from Ali Pacha.

Komentet